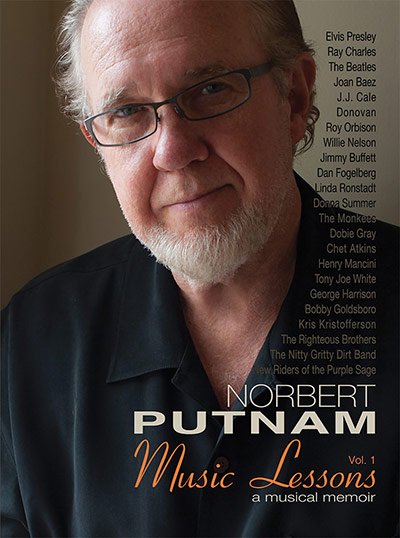

Interview with Bassist Norbert Putnam

October 9, 2021

Norbert Putnam (b. 1942) has had a long career in music. He was the first bassist to record in the fledgling Muscle Shoals recording scene, playing on hits by Arthur Alexander, the Tams, Jimmy Hughes, and more. In 1963, he recorded the #3 hit “Everybody” with Tommy Roe, and the following year he accompanied Roe as the opening act on the Beatles’ first U.S. tour. Putnam relocated to Nashville in 1965, where he eventually became a top-call session musician. Notably, over the course of the 1970s, he played on approximately 120 of Elvis Presley’s studio recordings. After co-founding Quadrafonic Sound Studio in 1971, he also established a successful career as a producer, working with artists such as Joan Baez, Dan Fogelberg, and Jimmy Buffett.

In October 2021, I sat down with Putnam to discuss his career and the ins and outs of session work.

Brian F. Wright: Norbert, thank you for speaking with me. Can we start with how you first got into playing bass?

Norbert Putnam: When I was 15, some kids in my school started a band to play early Elvis and Sun Records. My father had played country bass on Beale Street when he was young. So, we had an [upright] bass in the house, and those kids said to me, “You’re the bass player. No one else in school has one.” So I played slap acoustic bass and that was all cool. We loved that. But then I turned 16 and I meet [drummer] Jerry Carrigan. He joined the band and we switched from playing Elvis to music that we could play at the fraternity parties at Ole Miss, Alabama, and Auburn. This is big money. I can make $25 at Ole Miss, and another $25 the next night at the University of Alabama. My father only made $150 a week! This is huge cash. And so my dad helped me get an electric bass. I ordered a 1958 Fender Precision Bass, with the gold anodized front. I had to wait four months to get it, and when it arrived, it had a black pickguard! I said they sent me the wrong one! [Laughs] But I was stuck with it.

BW: Did you get a Fender Bassman with it?

NP: Yup. It had four 10” Jensen speakers and I built a bass reflex cabinet to increase the bass response. It would just snap onto the back. But about a year later, I got an Ampeg B-15. And that's what I used in the studios. All the way up through Nashville, I used that same Ampeg B-15.

BW: There weren’t that many people playing electric bass in 1958. Had you seen one in person before?

NP: A lot of the road shows would come through Florence, like the Dick Clark Caravan of Stars. I remember seeing Ray Charles and the Raelettes at the Florence Coliseum. And I remember seeing these guys play those early Telecaster-type basses. And you could hear it!

BW: How long after you started playing electric did you start to record?

NP: Tom Stafford started a publishing company. We were 16. Every day after school, we would go up there. Tom was like Robert Preston in the Music Man: “Right here in River City, we’re going to start recording!” We thought he was delusional, but you know everything he said came true. He would sign anybody that could make a rhyme. The songs were awful but were learning how to come up with our own parts. Every bass line that I played at Auburn, I took off the record. And now I'm charged with finding a [new] bass line to fit the vocal. So it was a good training ground.

BW: You mentioned in your book that Stafford didn’t pay you in money, but rather in swigs of cough syrup and movie tickets.

NP: Yes! But that was a better deal, we thought. We had two movie theaters and saw everything. The thing about it was, Stafford was the one who instilled in us this idea that it was possible, in a little town like Florence, Alabama, to make and record our own music. And when Rick Hall came along two years later, we'd done some demos with Arthur Alexander. Arthur was the first guy to come up the steps who had great songs, and he could sing well. And he was a handsome guy. So Rick hears Arthur and says to Tom Stafford, “I will build the studio and produce this guy.” Rick Hall was the entrepreneur, you see. Nobody else was thinking about building a studio. He leased space over in Ford City, an old, abandoned area. All Rick had was two mono tape machines, four microphones, and a mixer. He had a Fender Bassman on the floor, which he used as a monitor. You had to sit on the floor in front of it to really hear the full bandwidth! So, we go over there, and he's got Arthur and we’ve got a rhythm guitar player standing on a couple of wooden crates on the other side of Arthur’s U47 [microphone]. And he’s playing guitar and Rick would shout, “Back up!” So we’d move everything back a little bit. He’d start playing again, and Rick would say, “No. Go forward!” You see, he was balancing the lead vocal and the rhythm guitar on this one mic. And Terry Thompson and I, our amps were in a V-shape, with one Electro-Voice dynamic mic in-between. And Rick’s shouting at me, “Raise the bass!” “No, down a little bit.” And we had one mic stuffed down in the piano. Over Carrigan’s drums he used a cheap Crystal mic, and when Carrigan would hit the hi-hat, it would distort totally. We played that song 35 or 40 times before Rick was able to balance it. He had never engineered a record and, guess what, he becomes an excellent engineer.

The original Muscle Shoals rhythm section at FAME Studio in 1963 (Putnam is on the bottom right)

BW: You were in the studio, just learning as you went.

NP: Yeah, but he would wear us out. A lot of times the singer might get it on the fourth or fifth take, and he didn't even notice that. He's still working on the balance. Somewhere around 40 or 50 takes, he'd say, “Well, let's do one.” And by that point the singer’s exhausted! [Laughs]

BW: So once FAME opened, was that standard process? Did you walk in thinking you were going to work on one song for hours, doing 40 takes back-to-back?

NP: Yes. We hadn’t learned how to sketch out the songs yet. Now, after that first song [Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On”] is a hit, everything changes. [Pianist] David Briggs and I were suddenly looking at each other, thinking, “Could this actually be a career?” [Laughs] Because it had made it across the pond. Brian Epstein handed that record to John Lennon. And the Beatles did the B-Side [“A Shot of Rhythm and Blues”] and the Rolling Stones covered the A-side. And then, coming up from Atlanta, was the Tams and we did “What Kind of Fool (Do You Think I Am).” By the way, I’m playing acoustic bass on that. You know, the acoustic bass has a more powerful sound than the Fender bass, unless you mute the Fender bass heavily. That leaves a lot of room for the drums to play around. So I played acoustic bass on about half of the hits down here, and then I’d pick up the Fender bass if it really rocked out. And that continued when I went to Nashville.

BW: And that stock Fender bass you had came with a mute in it, right?

NP: Yeah. And as you played it a lot, the mute just fell apart. But I did take the cover off the pickup, so that I could rest my finger on it. Coming from the acoustic bass, I needed something to have my thumb on. But that bass was stolen as soon as I got to Nashville. I ran down to Hugo's Music, and I said, “Do you have a Fender Precision?” They had a ’65 model. It was the exact bass [design] as my ‘58. I put a set of strings on it. I played it that afternoon. I adjusted the neck that night. And you know what it sounded exactly like the other one. The pickups hadn’t changed. Now as the ‘70s went on, I put a Badass Bridge on it and a brass nut and then it really would sing.

BW: When you first started playing, were there particular electric bassists that influenced you?

NP: There were players, but I never knew who they were. Chubby Checker’s records had this incredible bass sound. Someone in Philadelphia played that. Hank Ballard and the Midnighters. You ever hear those records? That guy had to be a jazzer because he played these complicated lines, adding in sevenths and ninths. And so that got me thinking. By the third year over at FAME’s new studio, which they built in 1961, we were working with Tommy Roe, a bubblegum singer from Atlanta. And Ray Stevens, the country comedian, was also an arranger and orchestrator, and he’d arranged a whole a whole album for Tommy Roe. He hands me a bass line, and I’m looking at it, but I can’t read it. He hands Carrigan a drum part in six staves! And David, who had piano lessons but hadn’t been reading, said to him, “Could you play some of this for me?” So we all gather around the piano and Ray plays each of the parts. It turns out it was pretty simple, so we got it right away. He took us to dinner that night and told us, “You're young guys, you know how to play the young music, and Nashville is looking for a young rhythm section. If you can get your sight reading together, you can come to Nashville. And so I went out and bought Bob Haggard's bass method. And Rick Hall wanted David and I to write for horns, for when the Memphis Horns came down. So I also found an old book by a Hollywood guy named Russ Garcia. Years later, I’m in Nashville working with Henry Mancini and he drops a bass part, and I can read now. I can read, I can bow. I’ve been taking lessons. And he says, “Alright Norbert, play the paper. No adlibbing.” Well, he wrote the greatest bass lines in the world anyway. But I was talking to him, because he had come down to Nashville. He hired great soloists: Buddy Spicher, a country fiddler who could also read, a steel guitarist, and guitarist Grady Martin. Henry is playing piano and he’s got the full scores over there. And I said, “Would you mind if I looked at your scores?” And he said, “Do you write?” Well I was arranging a few things around town, Chet Atkins hired me for some stuff, and I wrote some stuff for Elvis. And he said, “Well, where did you go to school?” I said, “You won’t believe this, but I bought this book at the piano company in Nashville by Russ Garcia.” He said, “You read Russ’s book!” I said, “Yeah.” “Norbert, it’s the greatest book ever written on orchestration. I read that in high school!” Isn’t that the craziest thing you’ve ever heard?

BW: Rick was also a bass player, right? Did he ever give you specific instructions about what to play?

NP: No. I think he was too intimidated by me. He never said anything to me. He never changed a bass part, he never offered a bass part. I knew he played bass, but I never heard him play. He didn’t have any rudiments of music. He would have a song and an artist and sometimes the artist could play guitar and sing the song, you know, like Tommy Roe could. And we'd sketch it out and we would just start playing what we felt might fit. And the artist is smiling and the band is smiling, and Rick would sometimes come out and say, “I don’t like it.” And we'd probably been playing it for an hour or two. We’d say, “Well, what do you hear?” “I don’t know. What else can you do?” Well I could do lots of things, from James Jamerson and Hank Ballard stuff to Burt Bacharach and Fats Domino. So we’d say, “Can you narrow it down?” And he’d say, “Make it like a Drifters record.” That’s where Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On” came from, it was a total steal. And that was the way he usually made records.

BW: Do you remember how much Rick paid the musicians? Were you just getting a flat fee for the whole session?

NP: We were getting $5 an hour. Now here's what happened: We do that first record with Arthur [Alexander] and somebody paid us $5 an hour. But Rick goes up to Nashville and with the help of a payola disc jockey, he made a deal to get it on Dot Records. Dot had Pat Boone, a major star, right? And so the record came out and they put the money on it and it made the Top 20. And then Dot Records found out that the kids who played on it were not in the Union. And so suddenly a private plane comes down, picks us up, and takes us to Birmingham. And they paid for us to join the Musician’s Union. They paid the union scale and backdated the contract, and that’s how we became Union musicians, and we found out from Ray Stevens that in Nashville the session scale was about $50-$55. And he said, “You know you can play three or four of those a day.” You’re kidding! Every three hours you make $50. So we started making plans right then to get our sight reading together well enough to Nashville, and two years later that's exactly what we did.

BW: So, was there no Union presence in Florence?

NP: The closest office was Birmingham. They never came up. And this was important to Florence becoming a recording center. Because after we had that first hit record, Rick builds the studio, but no one is coming. Why would you go down there? But then Bill Lowery, of Lowery Music, comes along. He had a whole collection of great artists. Rick tells him, “Well, you can actually pay them $5 an hour. And they’ll play nine hours but sign for a three-hour session.” He thought that was a great deal, so he brought the Tams. We do a big record, “What Kind of Fool (Do You Think I Am),” and then Joe South comes, and Billy Joe Royal comes, and Ray Stevens and Jerry Reed are all part of Lowery’s thing. By the end, working for Rick, I was making $10,000 a year as a studio musician.

BW: How many days a week were you in the studio recording?

NP: At that point, five days a week, sometimes Saturday. When people started to come, it got to be… Well, first of all, we got better. Rick got faster. And Rick wasn't always the producer. Like Felton Jarvis produced “What Kind of Fool (Do You Think I Am).” And so that one wasn't 40-50 takes, it was probably more like seven or eight.

BW: At some point, working for Rick, did you start to realize that maybe you were getting swindled? That you should be getting paid more for this?

NP: Well, we talked about that as a group, but you have to understand, we knew we weren't ready to step into Nashville studios yet. We felt like we needed a couple more years to improve our speed and to learn to write out charts.

BW: There’s that story in your book, where as you’re about leave FAME, Rick tells you that you’ll never amount to anything. What did that feel like? Were you pissed off?

NP: Well, it confirmed my darkest suspicions. Rick was sitting there saying, “If you stay here, I’ll make you leader.” So it was mixed messages. Like, if I was so bad, why would he want me to stay? [Laughs]

BW: And then you left to go to Nashville?

NP: At first, working for Rick, we didn't have the skills that we needed to have to work in Nashville. But by the time we went left in 1965, I could sketch out a chart, and my first year there I made almost $50,000. What the Nashville people did was, we were sort of selected to be the new young group, but they didn’t tell us that. We were encouraged to come, and they said, “We’ll help you if we can, and we can maybe get you some demo accounts, which paid half scale. And, later on, Harold Bradley, said to me, “The reason we wanted you guys to do all those demos, is because they all came across Chet Atkins’s and Owen Bradley’s desks, and we could all watch your progress. And one-by-one they picked us off, they didn’t pick us as a rhythm section. And probably by the second year, if I did three sessions in a day, I played with three different drummers, three different pianists, twenty guitar players. And the Nashville guys, they could all play in dozens of styles of music convincingly. Owen Bradley made me play acoustic bass one Saturday at the Bell Meade Country Club. He forced me to do it. I said, “I can’t do it because I don’t know the music.” But he said, “Come on out, you can stand and watch my left hand.” I went out there and murdered the Great American Song Book, but at the end of evening he’s paying me my $25 and I’m apologizing. I’m thinking I’ll never see this guy again. But he said, “Kid, you found most of that.” It turns out it was a test, he wanted to see if I had good ears! And then, two weeks later, he askes me to play with his big band, and my bass book had 125 charts in it. And I’m a pretty good sight reader at this point, not great. But Owen stands up and says, “Let’s do 24, 37, and 82,” and just counts it off 1-2-3-4. And the band hits it! I’m looking through the book trying to find the chart. I find it, and lock in. At the break, [singer] Louis Nunley comes over to me and says, “I want you to know that we really enjoyed watching you on that first song. We always do that when we have a new member in the band, Owen calls out a song he knows we can all play.” [Laughs] So it was a baptism by fire.

BW: What were your early years in Nashville like? Were you just playing on demos, trying to get noticed?

NP: Yes! And it backfired on me! Honestly, I was not being conservative, I was trying to get them to look at me. And there was an arranger named Bill Justis, who was the best arranger in the city. And it had been two years and he’d never called me for anything. Then one day, he books me to do a session with Bobby Goldsboro, I think, who was a pretty big star. And so I go over to the big Columbia studio and it’s full of people. Back then, they did sessions live. If there are strings, they’re back there. If there were horns, they’re back there. And then they would mix it as we were playing, all down to three-track. Jack Gold from United Artists was in Nashville producing and he told us that “Justis is going to be a little late with the parts. So everybody get in your chairs, get in tune, and be ready. There’s strings, brass, a chorus, and percussion. Three guitar players. And me with my Fender Bass. So Justis comes in and he’s got all the parts hanging over his left arm and he’s rushing to hand them out. The very last stop is me and the chart is four pages long and all I had was one music stand. I look at the first four bars and I realize I can’t play it. It’s jumping octaves, it’s all over the place. Right then, I hear Justis count off 3, 4, and the band hits it, and I just choke. My first thought is, “By the end of today, the word will be out on the street, the kid can't sight read well enough he’s too slow.” And if that happened, you’d never see that guy again. So Justis stops the music and he looks at me and he goes, “Hey, you the kid from Muscle Shoals?” I was so embarrassed, I was all shades of red. And he looks at me and says, with his accent, “That not the part?” How the hell would I know? And then he says, “I tried to take it down the way you played it on the demo.” What? “I called [Bob] Beckham and said who the hell played this? I don’t want to try this with just anybody. And he says it was you.” “I played this?” He told Jack to play the first three bars and as soon as I heard it, I could play the whole damn thing. It was one of those boogaloo bass lines, that kind of thing. So I went from being almost out of the business to picking up the Goldsboro account! I ended up playing acoustic bass on “Honey,” “Little Green Apples,” “With Pen in Hand.” But that was the only time in my career that I ever faced a bass part that I couldn't play. And it was my own. [Laughs]

BW: But ultimately, it seems like your plan worked out. You were making a name for yourself.

NP: As I’m getting foot in the door and I’m getting more and more accounts, I figured I’ve got a three-hour session and in Nashville, you do four songs with two ten-minute breaks on the hour, But everything was done in three to five takes. All the singers could sing and the musicians could play! And it was just such an easy thing to do. But, it’s like going on stage: it’s five minutes before the session, you’re already in tune, you’re in the bathroom. I’d look in the mirror and say, “Putnam, you’ve got three hours to play two bars somewhere that impress this artist and this producer so much that they hire you again.” So I would go out there and play along, always looking for an opening. And if we came to a little interlude at the end of the second verse and the piano player or guitar player didn't do anything, I would jump up high and play a fill. And everyone would say, “Who the hell did that?” And so I had the reputation for occasionally playing a line that everybody liked.

BW: Well, this seems like a good time to talk about your philosophy of bass playing. You said to me earlier that you consider yourself the kind of bass player that serves the song. Can you talk about that a little more?

NP: Well, the first thing I think about is the singer. Their voice directs me to a style. I'm going to play a bass style that fits the voice and the genre, whether it's a folky kind of thing, like I did with Joan Baez or Ian & Sylvia. And that would sort of tell me where the boundaries were for what I might play for those three hours. If it was J.J. Cale, you listen to “After Midnight,” that little thing I'm playing in the intro, I’m only doing that because no one else was doing anything. So if the band would sit there, I would do something. And when I started to produce Dan Fogelberg, it was just his acoustic guitar or his piano, my bass, and a drummer. And he would encourage me to play something over the intro. Sometimes, with Dan, I would double something that I heard him do on the guitar. But I’d only do this in the intro. As soon as that vocal came in, you hear me drop back down to that bottom octave. Owen Bradley said to me, that night after I screwed up all that music, he said, “Now kid, I’m going to make you third bass at Decca. You got good ears. I want you to come over the office and I'm going to give you a stack of records that Bobby Moore has done for me and a stack of records that Junior Huskey has done for me. I want you to look at it.” Well, I wrote out some of their stuff, because I have a better photographic memory than anything else, and so, when I got called I had to go in to be Bobby or Junior. But Owen said to me, “Do you know what we do?” I said, “I don’t know Mr. Bradley, you tell me.” And he said this very emphatically, “We accompany singers. Don’t you ever play one of those hot Muscle Shoals licks over my singer’s voice. You bring that acoustic bass. You leave that fucking Fender Bass at home.” And I said, “Yes, sir, Mr. Bradley.” [Laughs]

BW: So then you’re playing at Decca, but also freelancing all over town?

NP: Yeah. Every musician in Nashville was self-employed.

BW: It’s also a pretty small town too? When we’re talking about electric bass players, there’s maybe, what, four that are top call?

NP: When I came to town Charlie McCoy was Nashville’s first call Fender Bass player. And I came in the studio and Charlie came over to me and he sort of threw his arms around me and said, “Thank God you're here. I'll never have to play the Fender Bass again!” [Laughs] So I became the most called player on the Fender. I sort of filled that void.

BW: And for you, in some ways, the fact that you can play electric bass is another way for you to get your foot in the door?

NP: Yeah, but the acoustic bass made me more money for the first few years. Because Chet [Atkins] and Owen [Bradley] both still preferred it.

BW: Well, and you eventually became a producer yourself. What lessons did you take away from working with Chet and Owen?

NP: For five years, I had worked with the greatest producers in Nashville. Owen Bradley, Bob Montgomery, all had incredible ears. So, I had a chance to watch the great ones, and I really suffered through the bad ones. The bad ones would come out and say, “Hey Norbert, why don’t you play this?” And they’d go around the room and it would be the most vanilla arrangement you’d ever heard. But the smart ones… Owen would sit and the piano and a girl would sing and he’d turn to Grady [Martin] and say, “Play the turnaround going from the first verse into the second verse.” He’d tell them where to play. “Come in on bar nine.” These Nashville people had it down. Floyd told me that Owen had taught him a lot of the jazz stuff. Because Owen was a pianist in the style of Duke Ellington and Count Basie. And he was responsible for that soft Nashville Sound that he put together.

BW: With Harold Bradley on Tic-Tac too.

NP: Yes! When I would record for Owen, I would play with Harold and he’d play unison with my acoustic bass. And I’ve been studying these parts. But I said, “If you hear me do anything stupid on the run down, let me know.” And many times, Owen would say, “Let’s make one,” and Harold would tell me, “Hey, Norbert. That thing you're doing going into the second chorus, don't do that, do this.” And I’d go and write it down as fast as I could.

BW: And in those sessions, you’d just be filling in for what Bob Moore would normally do.

NP: Yes! And he’d knew everything Bobby would do, you see. We were working with Al Hirt, doing Broadway tunes. And this chart comes up, “Promises, Promises,” by Burt Bacharach. In the middle, just for the fun of it, writes like a bar of 11/12, followed by 5/4, followed by 7/8 or something. And we get to that part and I just stop playing. But Harold is playing. So we get through it, and I say, “Harold play those three bars for me, so I can count it.” Well, he goes, “Listen up” and plays it. So, I make it through “Promises, Promises” successfully, and for years after Harold retired, I’d see him at a party and I’d say, “Did I ever thank you for saving my ass on ‘Promises, Promises’?” And he’d say, “Every time you see me...” [Laughs]

BW: And that’s what’s interesting about a session musician, it’s a new thing every day. It’s different every time.

NP: Yes!

BW: What was it like to record with Elvis on those 1970 “Marathon” sessions?

Norbert Putnam: We did 35 tracks in 5 nights, working about 6 hours a night. You know what the Nashville secret weapon was, don’t you? All the musicians, when the demo was being played, would grab a legal pad and sketch it out in numbers, rather than letters. And if there was a syncopation that I thought they might want, I’d scratch out five lines and make a bar and point it to a I chord or something. So we would pretty much know the syncopation and the chord progression, and I’d also take down the bass line that was on the demo, in case Elvis wanted that. Now, in the studio, Elvis would listen to that demo a couple of times, sometimes three times, and the musicians would gather round and start talking about the arrangement. And he would turn around and say, “You guys got that?” And we’d say, “I think so. What key do you want to do it in? [The demo] was in E-Flat.” “That’s too low,” he’d say. We’d bring it up to E, then F. So then you’d write F over your numbers and everything works, and Nashville could instantly accompany a singer without a rehearsal because we wrote our own charts. And that’s how we were able to do 35 tracks in 5 nights.

Photo taken during Elvis Presley’s June 1970 “Marathon” sessions in Nashville (Putnam is standing to the left of Elvis)

BW: How strictly were you following the demo bass lines?

NP: Not totally strict. Listening to the demo, you’d get familiar with it. But I’d say that probably 80-90% of the time I invented a bass part that I thought would fit. And, you know, I played on 120 tracks for Elvis over seven years and he never changed a note. There were times I thought he wasn't listening. He was so intent about his vocal and we just had to hang on. He never worked his way up to the vocal. He started full out. He'd say, “Okay guys. Let’s get it on the first take.”

BW: And did you actually get it down on the first take?

NP: Well first, we’d play it down once, for Elvis and the engineer to hear, and then Elvis would say “Let’s make one!” After that, he’d go to the control room and listen, and the musicians would go in there one-by-one and stand beside him. Invariably, he’d say, “Hey Putt, what do you think?” And I’d say, “You think you could do one more for me?” “What are you talking about?,” he’d say. “Well, I want to do a thing on the chorus and David wants to swap out with James Burton.” And he’d say, “Alright. Let’s do it! Felton, guys, we’re doing it again!” And he’d rush back out and, you know what, do two or three more takes for us. One night I walked in there and he looked at me and goes, “Oh, you want to see me do it again, don’t you?” [Laughs] He was not one of those singers who said, “Well, I don't think I can do it again.” That was sort of the way the dates went, and they went quickly. He would stand in front of us, holding an [Electro-Voice] RE15 dynamic mic, which is what he used on stage in Vegas. He’s standing in front of the drums and the bass and everything, and it sorted of just worked out, because he was very emphatic with his singing. We were looking at him, he was looking at us. And, boy, sometimes he’d get all worked up, breathing deeply you know. We just looked around and thought, “Okay. Hang on guys.”

BW: And Elvis is coming off his big Vegas comeback at that point, and those tunes you are recording are sort of designed to be played in Vegas?

NP: Oh, absolutely. And there was one other thing: he goes out there to Vegas the year before, I guess, and he looks around and there’s an orchestra back there. Well, the hotel employed those guys year-round, and when they started pulling out some of the charts for his records and he heard the band, he loved it. A lot of these guys, these critics in the last twenty years have said that Felton Jarvis forced him to have a big orchestra on his recordings, and that those records should have been like Scotty [Moore] and Bill [Black]. No! Elvis called all the shots, and Elvis approved every record. When he did a big ballad, he loved having an orchestra.

BW: They just did that big reissue of the Nashville Marathon sessions a couple years ago, and they specifically took off the orchestra. Do you have complicated feelings about that?

NP: Absolutely, absolutely. Because Elvis approved those recordings. Every one of them. And he was a master. For them to say that Felton or the band made him do this, that’s just not true. They’ve sent me those box sets, and I don’t like the way they sound. I just give them away to people.

BW: Shortly after those Elvis sessions, you decided to open up your own studio. Why?

NP: You see, David [Briggs] and I both wanted out. Because I had played 625 record dates in 1970. My wife counted it up. I made over $100,000 that year. But my back hurt! [Laughs] So David and I had built Quadrafonic Sound Studio to be a demo studio for our publishing company. Then Elliot Mazer comes over to see our little studio in this old house and he loved it. It had two parlors with pocket doors, and then around where the kitchen was, we decided to have drum booth with an electric window that went up and down. There wasn’t a drum booth in Nashville until we did one in 1970! And we put glass in the pocket doors. So Elliot said, “Why don’t you put in a 16-track and some decent gear, and I'll bring Neil Young in here.” We almost didn’t do it. David and I were actually planning on writing country songs until Elliot shows up. But he said, “I’ll be a partner. I’ll put money into it.” So we put in a Quad Eight console from California.

BW: And that’s a huge board for Nashville for that era?

NP: Yes. It had twenty inputs! For most of the recordings that we did in the sixties at RCA Studio B, it was a twelve-input console. And Owen Bradley only had twelve mics. But we got that big old Ampex, so you know you got eight of the big modules up there that take up a full rack space and, down on the bottom, eight more.

Putnam at Quadrafonic Sound Studio with a sleeping Joan Baez

BW: And Joan Baez was the first big act you recorded there?

NP: I got lucky: David and I had helped Kris Kristofferson get his first deal. And I had introduced him to Joan Baez. I had been playing on her albums. And she calls me and says, “I’m coming back to Nashville. Kris has been out here and we’ve been writing songs together. And I want to record in Nashville and have you lead the band.” She really wanted some of the young players. So, I said, “I’d love to. Is Kris producing?” “Yes, Kris is going to produce.” Well I knew him to be rather shy in the studio. And I said, “Would you come to our new studio.” I’m telling you, the paint isn’t even dry! So, about two months later, I booked a great band for the session, all the Area Code 615 guys, like Charlie McCoy. I ask her how many songs they are planning to do and she tells me, 24 songs, it’s a double record. I was thinking of it as kind of a pop record, so I booked five sessions a day for five days. Charlie was pissed. He said, “What the hell are we going to do with the downtime? Are you telling me we can’t do 24 songs in two days or something?” And, of course, we probably could, you know. But Joan came to the studio at two o’clock and Kris is in the back with coffee machine, wedged into a corner so he can’t fall down. And he is, shall we say, highly inebriated. So I go up to him and say, “You know Kris, I don’t want you to worry about anything. Here's what you do as a producer. You go in the control room and you don't say anything, and this band will make her a hit record.” And you could do that in Nashville. I used to see Chet walk out of the room when we started to run a track down. And the band really could do it. These guys all wanted to make a great record with whoever they were working with. But Kris says, “I’m not doing it.” So what am I going to do, cancel 15 guys? They will kill me. I said, “No, no, no. You can do it.” And then he says, “I talked to Joanie and we think you should do it.” Three nights later, do you guys know this tune, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”? I had never heard it. Studio musicians don’t have time to listen to the radio really. She already had an arrangement of it. She played the guitar live with the rhythm section in time, and we did the vocal live and got in on the third take.

BW: Well, Norbert, it looks like we are out of time. Thank you so much for speaking with me.

NP: Thanks!